Otho Holland Williams and the Letter to Josias Hall

The essence of writing history is finding good, original source materials. As I have bemoaned many times, the authors of secondary sources can have agendas that distort, spin, and reassemble facts in ways that might shock the actual eyewitnesses. In dealing with the Battle of Guilford Courthouse, an excellent original source surfaced hundreds of years after the battle, and can provide important insights into the campaign.

Colonel Otho Holland Williams was a Maryland Continental officer. He had served in the southern theater since mid-1780, when George Washington sent the Maryland troops to bolster the southern army after the losses at Charleston in May. Williams served both as a commander and staff officer under Gates and Greene. At Guilford Courthouse, he commanded the Maryland brigade and acted as Greene’s adjutant general. As commander, he was involved in the maneuvers that preceded the 2nd Maryland’s headlong retreat from the battle. As adjutant general, he prepared the report of casualties after the battle, a central piece of the case against the North Carolina militia.

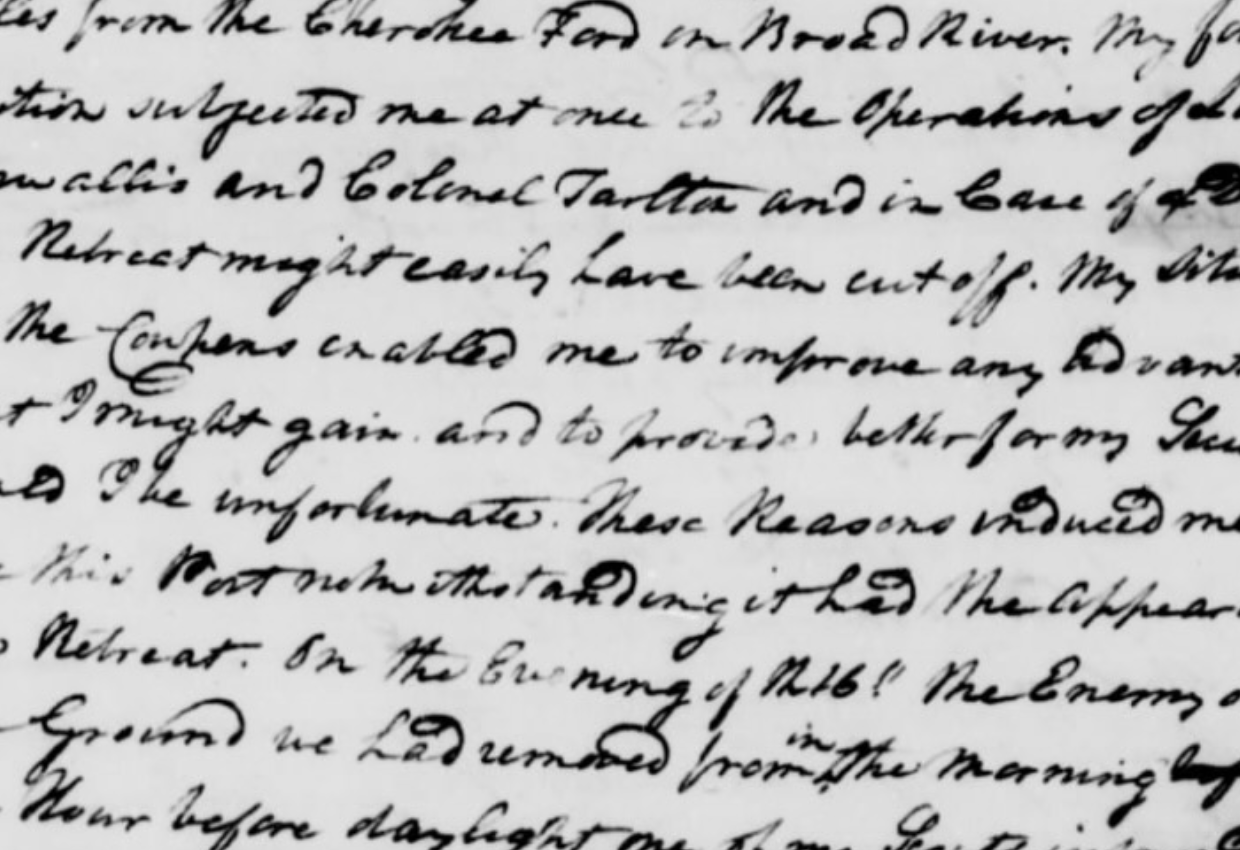

Two days after the battle, Williams wrote a letter to a friend in Maryland, Dr. Josias Hall. The letter was in private hands until 1998, when it was purchased by a collector at auction, then turned over on permanent loan to the Greensboro Historical Museum. The letter remains on exhibit at the museum. At some point, a transcription of the letter was made by someone for Guilford Courthouse National Military Park. Several years ago, I scanned the transcription. This was before I knew much about making scans, and they bear the scars of my lack of proficiency.

The transcription may be accessed here.

The letter adds a great deal to the fund of knowledge about the battle. Williams was highly critical of the North Carolina militia. Many later authors have tried to rescue the reputation of the North Carolina units, but Williams is a road block to these efforts. He described the men as, “a multitude of the noneffective and disaffected inhabitants of North Carolina.” Not content to stop there, he was even more caustic when discussing their battlefield performance: the North Carolinians, “like sore-eyed men exposed to sunshine, shunned the light, and abandoned a secure position behind a fence.”

Another controversy in the battle was the performance of the Virginia militia. William R. Davie, who was present at the battle, wrote that only one of the two Virginia militia brigades fought, the other dissolved as quickly as the North Carolinians. General Greene was a famous dissenter, insisting both Virginia brigades fought well. Williams agreed with Greene, writing to his friend that both brigades, assisted by flanking troops, held the British advance in check so well that the day’s outcome hung in the balance “for a long time.”

On the third line of battle, he needed to deal with the default of one of his own, the 2nd Maryland Regiment, who ran from the field when confronted by the 2nd battalion of the Guards. Williams blamed two factors: first, the regiment had a large contingent of state troops recently inducted into the Continental service, Williams implying they lacked the training and discipline expected of regulars. Second, he blamed a shortage of officers. The regiment had only eight commissioned officers to command six companies of soldiers.

Williams’s complaint regarding the state troops is difficult to assess. Reinforcements came and went throughout the war, and the performance of the new men followed no distinct pattern. The matter of the officers, though, was in a different category. Maryland had recently provided a new regiment to the war in the south, usually called the Regiment Extra or Regiment Extraordinary. Its arrival in the south caused no small amount of controversy. The veteran Continental officers were determined not to be led by higher-ranking officers new to the fight, and they protested the intention of the Maryland legislature to integrate the new regiment into the Continental line. Greene resolved the problem in the days immediately preceding Guilford Courthouse by integrating the new levies and the veteran troops into both Maryland regiments. His integration, however, involved only the rank and file. He sent the new officers home. While this may have assuaged the feelings of the veteran officers, as Williams pointed out, the act had unintended consequences. Having sent home a raft of officers on 10 March, he was drastically short of officers on the field five days later.

A final point in Williams’s letter also deals with the 2nd Maryland Regiment. One of the continuing mysteries of the battle was the reason they abandoned the battlefield. Most authors agreed with Lee that the regiment ran away “unaccountably.” William Davie was one of few who hazarded an explanation. He wrote that Colonel Benjamin Ford, the regimental commander, ordered a charge, which Colonel Williams, as brigade commander, overrrode. The men were recalled back into line under heavy enemy fire. They were ordered to advance a second time, and, as Davie told the story, “they all faced about” and left the field. A protest, perhaps, against the conflicting orders. Davie’s version has gained little traction over the years from historians, but Williams vouched for at least part of it. He mentioned nothing about the 2nd Maryland’s abandonment of the field, but did say they “refused to charge when ordered.” There was no mention of conflicting orders between him and Ford, but he did agree with Davie that the precipitating event was an order to advance.

Williams letter has not been publicized to any great extent, and the history of the battle is the poorer for it. I have posted the transcription, and hopefully this will make the letter available to more people interested in the battle.