Hunting Creek

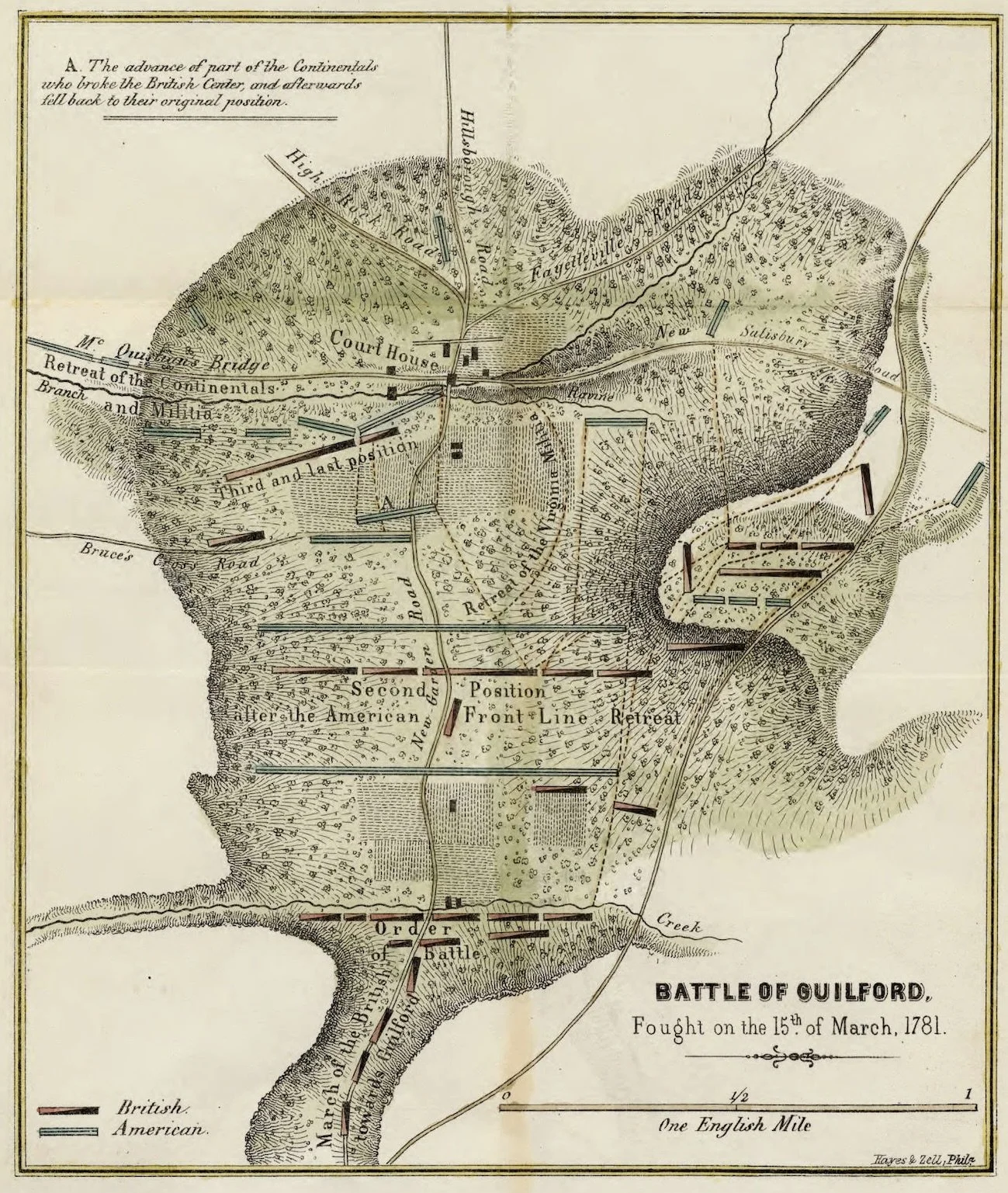

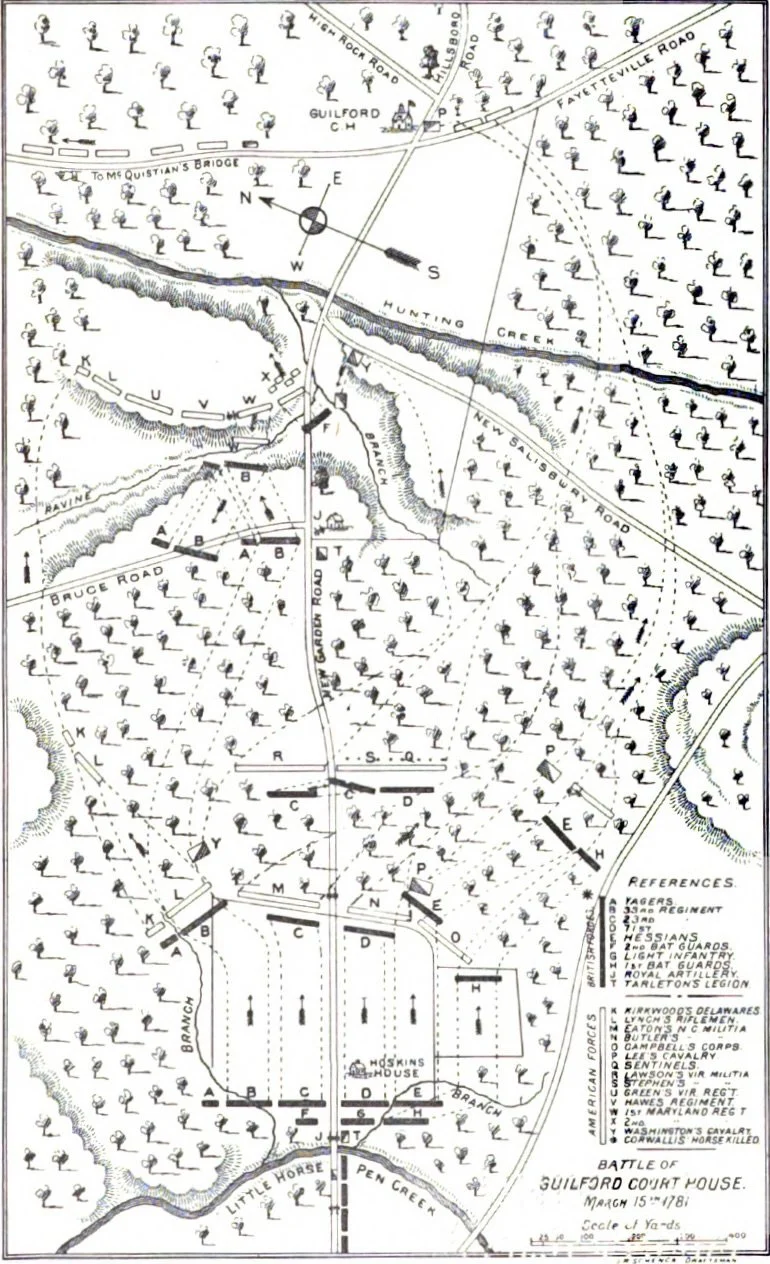

A great deal of ink has been spilled on the question of the location of the third line of battle at the Battle of Guilford Courthouse. The first and second lines have received a historical consensus, but the third line has been the subject of much controversy. In the middle of the nineteenth century, Rev. Eli W. Caruthers walked the battlefield with the few surviving veterans of the battle living in the area. He produced a map of the battlefield that remains, in my estimation, the gold standard for all of them.

A generation later, Judge David Schenck walked the area with Caruthers’s map. In Schenck’s time, all the veterans had passed on, but some of the physical aspects of the site remained. Schenck described building foundations and roads, now long gone, but evident to him and dating to the days of the battle. Schenck was the driver behind the creation of the military park. His reconstruction, similar in many ways to Caruthers’s map, became the accepted basis for the official park version of the battlefield.

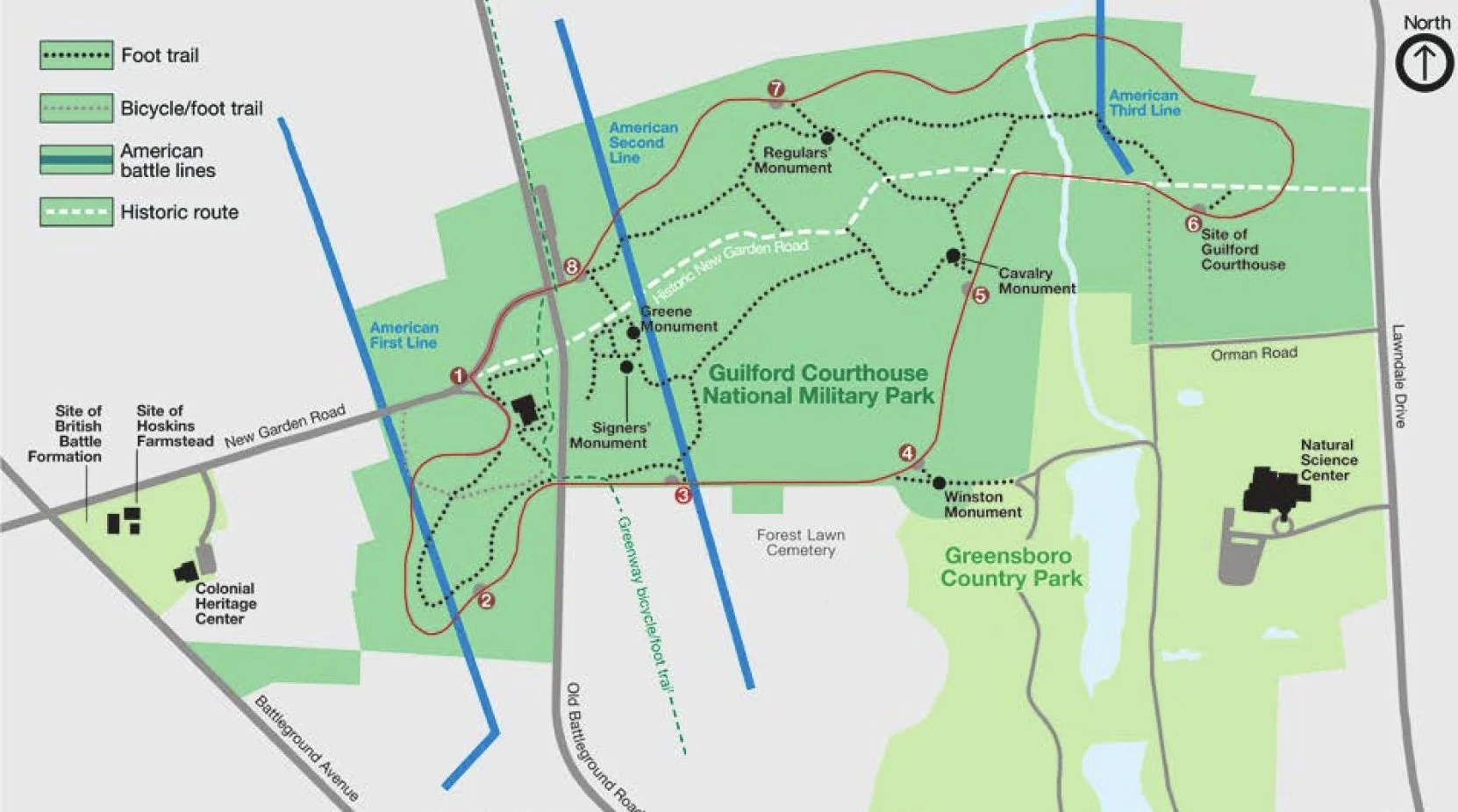

In the latter part of the nineteenth century, a group of local historians and park employees began to work on a new reconstruction. It left untouched the first and second battle lines from the Schenck reconstruction. However, it produced a radical change in the thinking about the third line. Previously, the third line had resided on the west side of Hunting Creek. Now, the third line moved 400 yards west, over the creek and distant from the rest of the action.

I have taken great exception to the new reconstruction of the battlefield. At bottom, placing the third line of battle east of the creek lacks any sort of historical foundation. It also lacks common sense. Hunting Creek formed a formidable barrier to foot traffic as well as to wheeled vehicles, yet there was not a single mention of it in any of the many battlefield memoirs. Had it been in the middle of the battlefield as posited in the new reconstruction, surely someone would have noticed it.

Before we start our journey through the literature of the third line battle, some basics. The centerpiece of the debate on the third line is Hunting Creek. Hunting Creek is the dominant terrain feature in the eastern sector of the battlefield. It has traveled under many names. “Richland Creek” is the official name, and the one that appears on modern maps, including Google Maps. “Bloody Run” shows up in some sources, and “Wilfong Creek” has mysteriously appeared in one writing. “Hunting Creek” is the historical name, and the one traditionally used in discussing the battle.

The main branch of Hunting Creek flows from Greensboro Country Park, through two artificial lakes, into Guilford Courthouse National Military Park. The dams have restricted the flow of water in the stream, and the creek is much less formidable today than it was at the time of the battle.

The creek has a tributary, flowing from the area of Forest Lawn Cemetery. The illustration above shows two tributaries in a single line. The map may be right, but having walked the area many times, I can safely say that those of us who are not hydrologists only see one. John Hiatt, in his masterful work on the park, well stated the course of the stream: cutting a path through the park’s eastern half, “Hunting Creek runs roughly south to north, while its tributary meanders from the southwest to the northeast, spilling into the former at an oblique angel near the Park’s northern boundary.”

In the region of the battle, Hunting Creek and its tributary are about eight to ten feet across, normally shallow, but as much as two feet deep in parts. The battle took place in a time of rainy weather, so the creek would have been running high. The most notable aspect of the creek is the steep bank on either side; in places the bank, completely perpendicular, is over a person’s head. The banks are native red clay, impossibly slippery when wet, which they always are in wet weather.

I’m six feet, two inches tall, and the bank is over my head.

Nothing about the creek is insurmountable. Unless, of course, one tries to cross the creek while under enemy fire, and this presents the essential quandary of the park’s modern reconstruction of the battlefield. In this second reconstruction, the Americans were deployed behind the creek, positioned to deliver deadly fire to any British soldier in the slick, muddy trap of Hunting Creek.

The second reconstruction is riddled with contradictions and errors. One obvious problem arose in the battlefield memoirs. The British battlefield memoirs made much of the mud that impeded their approach to the first line of battle. The ground in front of the American first line was “a field lately ploughed, which was wet and muddy from the rains which had recently fallen.”

In dry weeather, the creek is not impressive, but the ravine is always a beast

Here is the British complaint about the much worse conditions in front of the American third line: ____. Okay, that was a cheap shot. The British made no comments of any sort about crossing two slick banks and ten feet of water while under enemy fire. Hunting Creek made no entry into any of the battlefield memoirs. The logical conclusion, of course, is that the second reconstruction is in error.

The Americans did not line up behind Hunting Creek. Caruthers and Schenck were right: the third line was in front of the creek, not behind it. The British crossed open, dry ground to reach the American third line. The Americans counterattacked across the same dry ground. No one made an impossible slog over slick, red clay and dirty water.

To reinforce the point, one final photo. This one was taken a dozen yards north of the confluence of the creek and its tributary. In the first reconstruction, the location was nowhere near the fighting. In the second reconstruction, it was in the middle of the action:

The British would have advanced over the high ground behind me, over the top, then down the cliff face into the creek. Then, they needed to cross the ravine and go up the opposing bank into the American third line. All of this seems difficult at the best of times, but remember they were to have done all this while under heavy enemy fire. The British soldiers would have been silhouetted perfectly on the top of the high ground and while scaling down the cliff. Yet, somehow, this whole process failed to achieve any mention in any memoir, British or American. Not only were the British too smart to attempt a fool’s maneuver like this one, if they had survived it, they would have bragged about it.