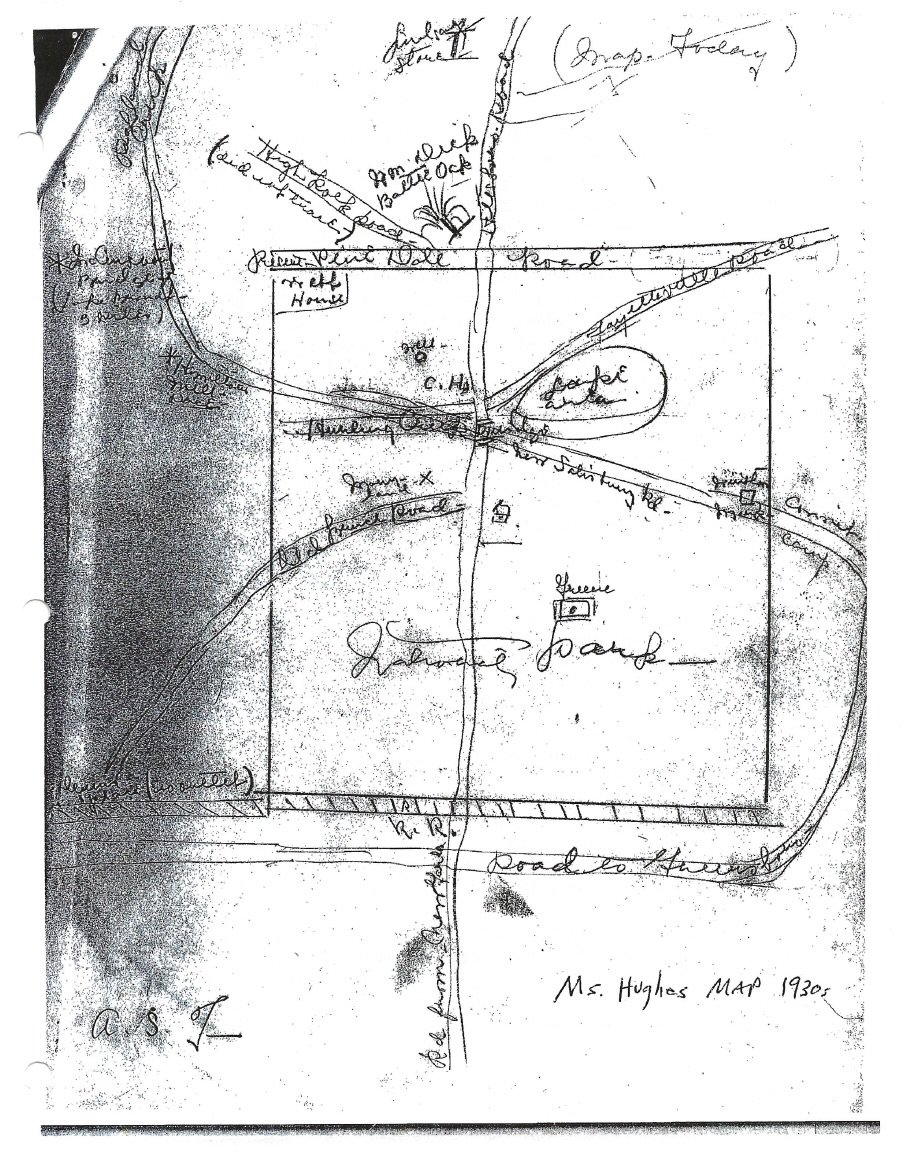

The Minnie Webb Hughes Map of Guilford Courthouse

I have gone into a great deal of detail about the maps of the Guilford Courthouse battlefield. Of the many entries, the frankly silliest is the sketch by Minnie Webb Hughes, drawn many years ago as part of an investigation into the battle and the battlefield. I should clarify the preceding sentence. The map is not silly; it was an honest effort by the last remaining eyewitness to see any remains of Martinville above ground. No, the absurdity came from later historians who drastically, even comically, overread Ms. Hughes’s scribble. An example: John Durham, in his 2004 paper, discussed the location of the John Hamilton millrace. He stated, “Ms. Hughes’ map depicts the race just north (one-half mile north of the intersection of New Garden and Hunting Creek) of the old park boundary.” The map is reproduced above. I defy anyone to find one-half mile, or indeed any distance, delineated on her map. The problem, of course, was that Durham went on to invest the Hughes map with even more credibility, relying on it heavily in his efforts to locate the courthouse.

Some background is in order. Ms. Hughes was a member of the Webb family, a name that figured prominently in the history and lore of Guilford Courthouse. Her father, James Webb, worked as a caretaker for the Guilford Battle Ground Company. In 1886, he purchased land in the area of the traditional courthouse site to use as a residence. She recalled her father repurposing building stones he found on the property to use in his house’s foundation. She recalled the courthouse and the jail, insisting her father used the stones from the courthouse chimney to build a well.

The date of Ms. Hughes’s interview is unknown. Durham, a park historian in the 2000s, dated it to 1934. The master version of the statement, reproduced in Charles Hatch’s 1970 book, Guilford Courthouse and Its Environs, documented the date as 1954. Durham never published his findings, so we have no way to verify his conclusion on the date. It was supported, to an extent, by the Hatch version. It noted an “addendum” from 1938, suggesting strongly the original statement was older. It seems likely that Durham was right, and the 1954 date was an error, or represented some other fact, for example, the date the interviewer’s notes were reduced to typewritten form.

One odd fact in the mix is that Hatch published Hughes’s statement, but never mentioned a map. Until this page was posted, the only mention of the map in any literature was in Durham’s 2004 paper. I infer from this that Hatch was more impressed with the statement than the map. In any event, the map was included as an illustration to Durham’s paper. The original presumably exists, or existed, in the files of the Military Park.

In dealing with Hughes’s statement, one encounters frequent mention of the well that stood near the courthouse. The well was documented in other sources, but even so, the town could not have existed without a reliable, clean water supply. Hughes mentioned the well several times. In fact, the site she mentioned still exists; there is a round depression in the soil still visible today, close to the traditional courthouse site. Here is a recent photo of the site:

It does look like an abandoned well. It is circular, and still deep. It is maybe seventy-five yards from the traditional courthouse site. Except, as with much of the traditional lore of the courthouse, archaeology has told a more prosaic story. Park Service archaeologist John Cornelison dug the site in 1997, and determined the site was too new to be associated with the old courthouse. It was probably the cellar of a vanished building. As this relates to our story, this work casts much of what Ms. Hughes said into doubt. The lore of the battlefield abounds with anecdotes of relic troves, mass burials, and the lost courthouse. Thus far, the archaeologists have deflated the stories’ bright promise, and this includes those told by Ms. Hughes.

The map and narrative prepared by Minnie Webb Hughes will continue to fascinate those people with an interest in finding the lost dimensions of the battlefield and the courthouse. She was, after all, the last surviving eyewitness to see any of the remains of Martinville above ground. Nevertheless, her perceptions were clouded by stories. One ruined building may look much like another, and Ms. Hughes was in no position to say that this one was the courthouse, that one a house. She left a record valuable in its faithful rendition of the traditional view of locations for the courthouse, the jail, the Hamilton mill, and so forth. Although of interest, this is not the same thing as knowing their actual location.