The Haldane and Tarleton Maps of Guilford Courthouse, Part 2

This is the second of two posts on the Haldane and Tarleton maps of Guilford Courthouse. The first concluded the many maps going under the names “Haldane” and “Tarleton” had a common ancestor, a rough schematic of the battle archived in the Library of Congress. William Faden, the age’s master mapmaker, went to work on the rough draft and produced the map that illustrated Tarleton’s memoirs. This map is pictured above. A final map, found in the Clinton papers in the William L. Clements Library at the University of Michigan, is probably a handmade copy of the Faden engraving. The point is that all these maps are essentially identical in their material aspects, and to deal with one is to deal with all. This post will deal with some of the salient issues presented by the British military maps, and in doing so will address the map in Tarleton’s memoir, understanding it represents all of them.

The essential problem with the Tarleton map has been that historians have placed too much reliance on its details, reading into the work things never intended by its authors. John Durham provided a good example, one among too many: he insisted Tarleton depicted exactly 176 yards from the American third line formation to the courthouse. The map, of course, shows nothing of the sort. At best, the map is a sketch, which Tarleton intended to illustrate his narrative of the battle. Nothing in the map’s appearance or history suggests it was intended to sustain the overly close reading so many people have given it in later years.

The most prominent error in the map is the directional arrow in the lower right corner. It is fifty degrees off course. Durham, once more relying too heavily on the map, hypothesized a later editor added the arrow in a misguided effort to correct an oversight. He, again, was incorrect; the rough draft of the map in the Library of Congress shows the same directional arrow with the same mistake. No one has proffered a good excuse for the misdirected arrow. Brandon’s work on the map was directed at the arrow, and he, as with everyone else, was confounded by the obvious mistake, apparent to anyone with a compass.

Next in line is the road starting in the center of the bottom of the map, branching off Historic New Garden Road and traveling toward the map’s upper right corner. John Hiatt, in his masterful work on the battlefield park, tactfully stated that this road “has not been identified. None of the extant accounts of the battle make reference to this route.” In other words, it never existed. This was another puzzling mistake, an entirely gratuitous feature that added nothing of value.

At the same time, the map missed a major road. There was a road at the time to the town of Bruce’s Crossroads, present-day Summerfield. It intersected Historic New Garden Road between the second and third American lines, and should have been depicted traveling from the center road to the map’s left edge. This was a major road, and its omission once more baffles the viewer.

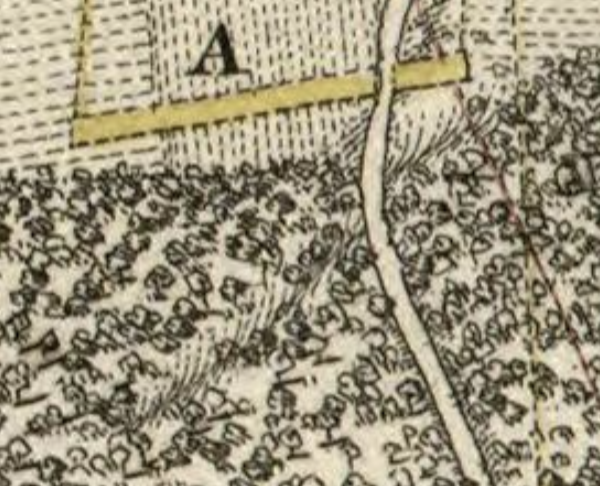

In devising the revised reconstruction of the battlefield, the revisers placed most reliance on the terrain around the third line. The original reconstruction placed the third line on high ground west of Hunting Creek. The revisers disagreed, and insisted the terrain east of the creek more accurately matched the landforms depicted on the Tarleton map. The revisers, of course, were wrong. Here is the terrain as shown on the Tarleton map:

The map showed the American third line on a hill whose southern terminus was on Historic New Garden Road. The hill had several protrusions, ending in a series of terraces on the northern face. The key is that the hillside protruded farther west as it moved north. On the ground, the reverse is true, and the land recedes eastward as it moves north. Recall that due to problems in orientation, the map shows east at the top, due north is on the left:

The above is a view of the same land on a modern topographic map. The orientation is the same, and Hunting Creek is the stream in the middle of the picture. The comparison is obvious: the land on the eastern bank of the creek recedes eastward as it moves north. There are other points, equally obvious. First, there is no landform matching the two-lobed hill in Tarleton’s depiction of the area. Second, the steep cliffs on the western bank of the creek match absolutely nothing on Tarleton’s map. Once more, we see that the map was at best a sketch, but more to the point here, it was a sketch of another piece of terrain.

Hunting Creek, of course, was the map’s most notorious omission. Durham, speaking for the revision, asserted that the stream was not “tactically significant,” and could therefore be eliminated from the battlefield map. Paradoxically, in the revised reconstruction, the ravine the creek traveled in was “tactically significant,” so any omission of the creek, or its banks, was a problem without any obvious solution. Unless one returned to the original reconstruction. As originally determined, the creek was to the far east of the battle, not involved in the action. Under the first reconstruction, Tarleton was at liberty to include or omit the creek; it was irrelevant to the fighting. However, the second reconstruction changed everything. By moving the fighting 400 yards east, it placed Hunting Creek directly in the middle of the third line action. It was beyond “tactically significant;” it became the most important terrain feature on the battlefield.

So, to recap the paradox: Hunting Creek was not tactically significant and could be left out of the map, until the revised reconstruction made it tactically significant, and its exclusion was mysterious and inexcusable. All well and good; we might chalk this problem up to one more defect in the map, but for one consideration. The foundation of the revised reconstruction was the absolute infallibility of the Tarleton map. If it was infallible, it needed to include the creek, as long as the revised reconstruction was right. If the revision was wrong, then the map returns to accuracy. As I said, a paradox. Its only resolution is to accept the first reconstruction. This way, the creek was distant from the action and had no place on the map, a position confirmed by the map.

One of the interesting points of the map is that some of its content is not visible to the naked eye. Faden, a master engraver, hid things only visible under magnification. One such feature is a small ravine in front of the American third line. Here it is in a magnified view:

This ravine appears in only one other map of the battlefield, the one prepared by David Schenck where he documented the first battlefield reconstruction. Here is a shot taken from Schenk’s map, showing the ravine, marked as such in the original:

This ravine still exists on the ground. It is apparent to anyone walking the battlefield, crossing in front of the Third Line Monument, crossing Historic New Garden Road, and running toward Hunting Creek, as depicted by Schenck. On Tarleton’s map, the ravine’s trajectory places Hunting Creek to the far right of the American third line, exactly where it should be.

There are legions of problems with the Tarleton map. Space prevents discussing all of them. For now, let’s leave it that the map was a sketch, intended to illustrate Tarleton’s narrative, and never destined for infallibility. The many errors reflect more on later generations of historians who tried to make the map support the revised reconstruction, an argument fallacious from its outset.