The Highlanders at Moore’s Creek Bridge

Many say the first engagement of the Revolutionary War in the south was the fighting at Moore’s Creek Bridge, North Carolina, on 27 February 1776. I understand the other argument, that the fighting started in South Carolina at Williamson’s Fort on 19–21 November 1775. Williamson’s Fort, after all, took place earlier. But the Battle of Moore’s Creek Bridge was more than one more encounter of the backcountry militia, an ongoing struggle that developed into a bloody civil war and burned acres of the south to the ground. The fighting at Moore’s Creek Bridge started, at least, in an effort to involve the royal governor, his troops, and the regular British army against American revolutionaries. The campaign involved more than the local militia, and a regiment of the Continental Army participated in the maneuvers leading up to the fighting. So, all in all, I tend to the view that Moore’s Creek Bridge was first.

Josiah Martin was the last royal governor of North Carolina. In the early months of 1775, he began to feel the push of rebellion, and it was bothersome. Martin, a fervent royalist, did whatever he could to suppress the Patriots, and while he had some modest successes, his efforts proved futile. By July 1775, he had abandoned his palace and taken residence on a British warship sitting at anchor on the Cape Fear River.

Martin failed to see his setbacks as proof of an error in his thinking. Like many of his peers, he believed the southern provinces, including his own, seethed with Tory sentiment and only needed a slight push to energize the populace into a show of support for the royal government. He drew on two bodies of Americans he believed would spearhead the Loyalist renaissance. The first were the Regulators, a group that had revolted against the colonial establishment in 1771. Their revolt, ultimately unsuccessful, ended in the hanging of several of the leaders. Martin believed that these men, having felt the harsh hand of British justice, had incentives to work tirelessly for British power.

He was entirely wrong, and his calls to arms to the Regulators were met largely with disinterest. The other group he targeted, however, proved a different matter entirely, because these were the Highlanders, legendary figures in the lore of North Carolina history. The settlement of the Highlanders formed around a core of British army veterans, many displaced after their support of Charles Edward Stuart in the Jacobite Rising of 1745. Flora MacDonald, the savior of Bonny Prince Charlie and another figure of legend, was married to a former British army officer and living with the Highlanders in Cross Creek, present-day Fayetteville. The Highlanders, many aged beyond military years, decided to make one last show for king and country. They were led by Donald MacDonald, himself so aged and infirm he would be unable to finish the brief campaign, freshly commissioned a brigadier general of North Carolina troops by Governor Martin.

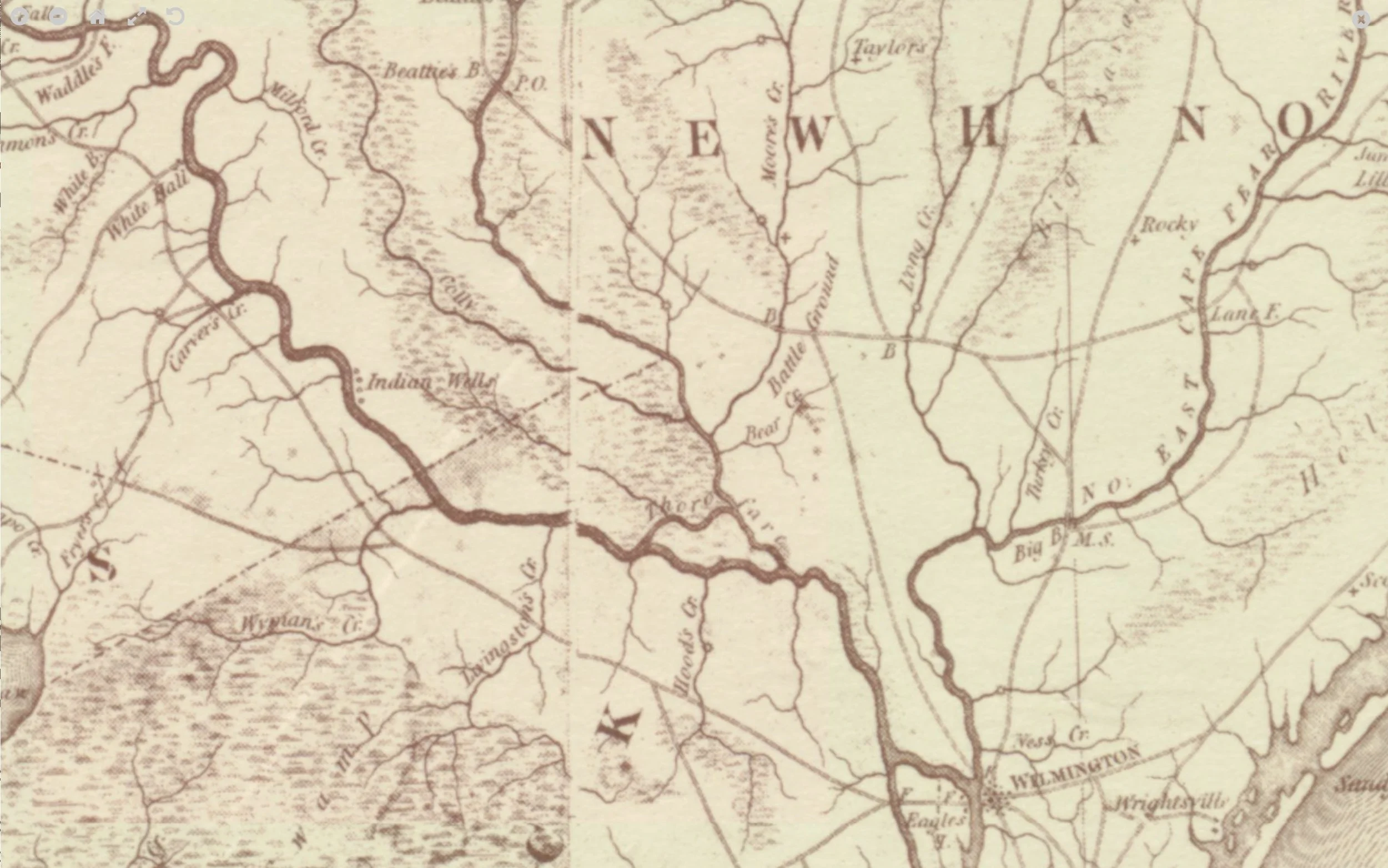

Martin had bigger problems than exile to a British warship. The Whig legislature raised the 1st North Carolina Regiment of the Continental Army as counties were empowering Patriot militia units. The government’s plan was simple on paper, but proved remarkably difficult on the ground. General MacDonald was to lead his force of 2,000 men from Cross Creek to Wilmington, at the mouth of the Cape Fear River, where he would meet seven regiments of the British army fresh from Ireland. The government planned a show of force that would shock the populace back into compliance with royal authority.

But MacDonald had to reach Wilmington, and in this effort he was opposed by the 1st North Carolina, led by Colonel James Moore, and two local militia regiments, led by Alexander Lillington and Richard Caswell. After a great deal of maneuvering, marked by proclamations and counter-proclamations between MacDonald and Moore, the two sides clashed at Moore’s Creek Bridge, a point thirty miles northwest of Wilmington, deep in the wet lowlands of present-day Pender County. The standard history of the battle is in J.P. McLean’s The Settlement of Scotch Highlanders in America Prior to the Peace of 1783 Together with Notices of Highland Regiments and Biographical Sketches. I like Hugh Rankin’s paper, “The Moore’s Creek Bridge Campaign, 1776,” in the January 1953 North Carolina Historical Review.

Both these works, as with any resource of quality on the subject, rely on a history of the campaign prepared by an anonymous participant, entitled “A Narrative of the Proceedings of a Body of Loyalists in North Carolina.” The original is in the North Carolina State Archives, British Records, CO 5/93, 80.28.1–10, Box 75, 25 April 1776. It is the single, indispensable primary source on the battle. Until now, it has been available only through the State Archives. For the first time, I have posted the document for everyone to read. It is posted as I received it. Some dedicated archivist added page numbers at some point in the past; otherwise it has been preserved as it was in 1776.

The Loyalist Narrative may be accessed here.

In reading McLean or Rankin, one is struck immediately by several inexplicable, incomprehensible aspects of the campaign. At the top of the list was the idea that the men in the Loyalist strike force assigned to cross the bridge into the Patriot entrenchments were armed with broadswords. Unthinkable to modern readers, the idea of raw courage appealed to the Highlanders, soldiers of the old school for whom firearms were an unpleasantness foisted on them by an uncaring, modern era.

On page 145 of the Loyalist Narrative, the author documented issuance of the broadswords to the soldiers. The author did not feel the need to document the courage of his fellows in making their charge against the Patriots, their muskets, and their artillery (yes, the Whigs had artillery to match the Tories’ broadswords). For this, one needs to consult the story told by Hugh MacDonald, memorialized by E.W. Caruthers in his Revolutionary Incidents and Sketches of Character: “every one of that company had his broad-sword drawn and marched in front, a little before day, to the bridge.” The author of the Loyalist Narrative did share one priceless point: the commander of the strike force assaulting over the bridge chose as his rallying cry, “King George and broadswords.” The broadsword, symbol as much as weapon, was irreplaceable to the Highlanders.

A transcription of the Loyalist Narrative may be accessed here.

Hopelessly outgunned, the Loyalist were resoundingly defeated in a fight of a few, fleeting moments. One of the most fascinating details to follow the battle was the tally of weapons captured by the victorious Whigs. The official count was 1,850 rifles and muskets, and while there are dissenting views on the tally, the point remains that the strike force leading the assault would have been the place to concentrate firepower rather than ignore it altogether.

The original document can challenge the reader. I have prepared a transcription, posted to this page with the original.