Archaeology at the Third Line

This is the fifth post in a series on the placement of the third line of battle at Guilford Courthouse. The series began with “Hunting Creek,” and continued through “Brandon,” “Durham,” and “Taylor.” The matter may be stated plainly: the archaeology conducted at the park strongly supports the original third line placement. There is, in fact, a complete absence of archaeological support for placing the third line east of Hunting Creek.

The official archaeology at the park is conducted under the aegis of the Southeast Archaeological Center (SEAC). All official digs and metal detector surveys have a SEAC acquisition number. With respect to the third line, the key work was supervised by archaeologist John Cornelison between 1995 and 2000, SEAC 1189, 1309.1, and 1487. All these found extensive numbers of battlefield relics at the site of the original third line site, none at the second.

Cornelison, and his colleague, Lou Groh, advocated the Park Service return to the original third line placement. Their position was entirely merited by their archaeology. The essential problem with archaeology and the third line placement was expressed well by John Hiatt in his monumental study of the park. He noted the archaeologists searched the area designated for the revised third line of battle, and “did not uncover any military material culture in the area.” The third line at Guilford Courthouse saw some of the hardest fighting in the war. It was, of course, inconceivable that the hardest fighting would leave exactly zero artifacts in the ground.

x

The problem of zero artifacts supporting the revised third line of battle is insurmountable. Nevertheless, much ink has been spilled in trying to justify the revised placement in the face of the overwhelming archaeological support for the original.

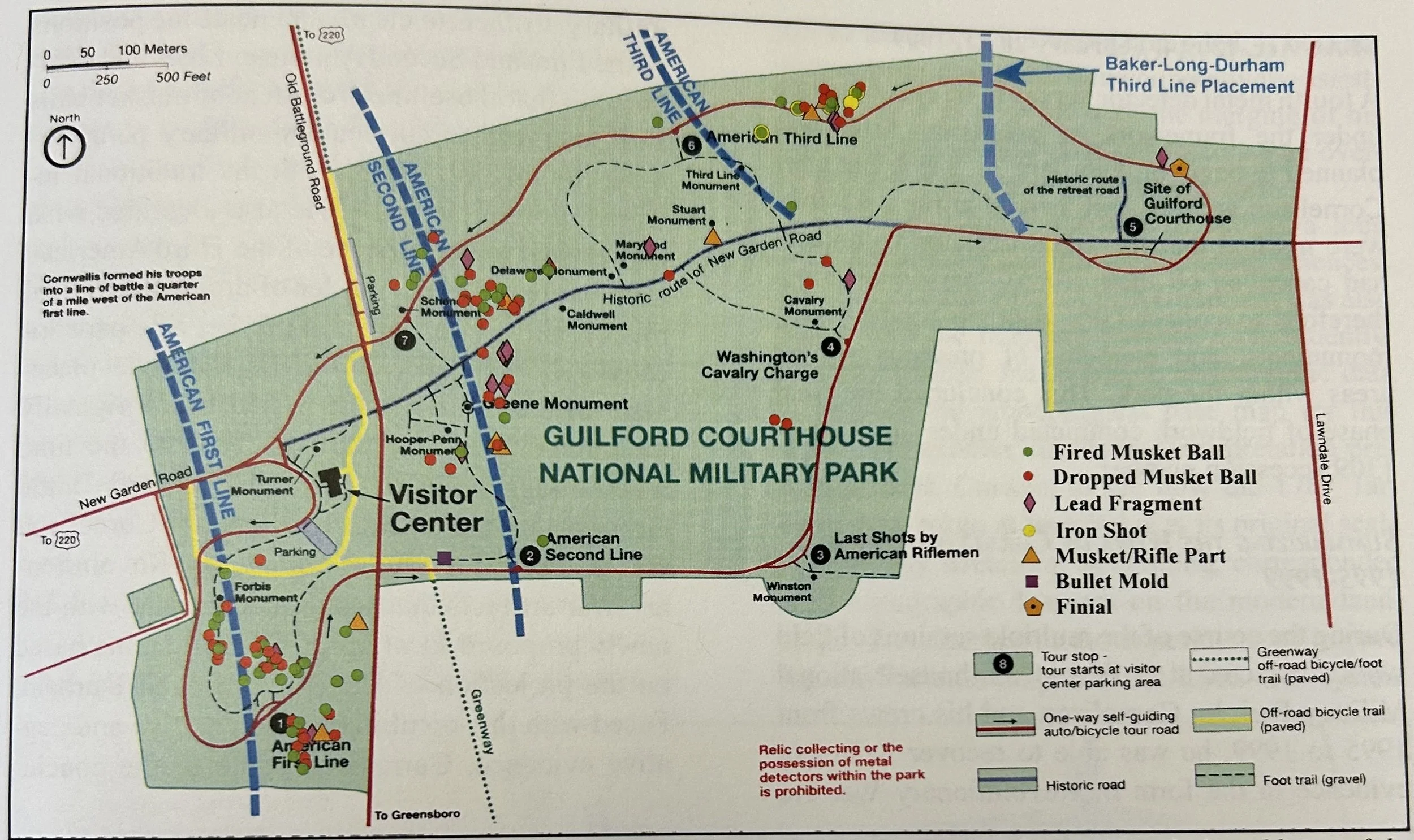

The stash of artifacts uncovered by Cornelison is best located on maps by reference to the tour road navigating the park. Tour stop five on the tour road is the American Third Line Monument. Moving east from this spot on the tour road, the road curves northward, then south, then makes a larger curve to the north before returning south to make its turn around the traditional site of the courthouse at tour stop six. Cornelison’s site is on the high ground north of the tour road in the southward curve east of tour stop five.

As I noted in the first post that started this series, the map drawn by Eli Caruthers in the middle of the nineteenth century was the most accurate. Cornelison’s work exactly confirmed the Caruthers map. Schenck’s placement of the third line was very close to Caruthers’s, and to confirm one was to endorse the other.

The Park Service, however, has now invested time and money in the revised third line placement. Bureaucracy moves, if at all, very slowly. The most recent authoritative pronouncement from the Park Service retained its support, albeit eroded, for the revised third line placement. The pronouncement, a two-volume publication entitled, Guilford Courthouse National Military Park, Archeological Overview and Assessment, asserted that Cornelison’s site actually marked the forward movement of the 1st Maryland Regiment’s counterattack.

This assertion, weak on its face, did nothing to solve the overwhelming problem: where were the artifacts establishing the third line in its new location? The Overview and Assessment did somersaults and backflips to find some justification for the revised placement. After considering several highly unlikely possibilities, the O & A finally concluded the reason for the lack of artifacts at the new third line was due to soil erosion on the slopes overlooking Hunting Creek, which buried artifacts on the lower slopes. The authors, as common sense required, admitted this excuse was “less than fully satisfying,” a point obvious to the rest of us.

The attribution of Cornelison’s site as the high water mark of the 1st Maryland’s counterattack was a tenuous, last-ditch effort to support a failing idea. The O & A stated the case: the Haldane, Tarleton, and Stedman maps showed the third line on high ground north of Historic New Garden Road, overlooking a valley west of the courthouse, its land cleared for plowing. When the 1st Maryland and Washington’s cavalry counterattacked, they moved forward until foiled by high ground dominated by British artillery. So far, so good. This much is exactly correct.

However, the O & A ruined its progress by asserting that the “only available” land in the park for the original position of the 1st Maryland was east of Hunting Creek, an assertion patently false. The whole point of Schenck’s reconstruction of the battle was that it took place in the wide, deep valley east of the American second line, the terrain described by Thomas Baker as a “great natural amphitheater.” The original third line was on one end of the valley. The 1st Maryland and the cavalry moved forward, toward the high ground formerly occupied by the second American line. After the fighting on the second line, the British artillery took over this high ground, a point made clear in the British accounts. The American counterattack moved forward until the attack failed to retake the high ground topped by the enemy cannons.

The archaeologists working at the park have failed to be daunted by the mistakes in the O & A. Two years after its publication, a team of archaeologists published a chapter in a book entitled, Digital Methods and Remote Sensing in Archaeology: Archaeology in the Age of Sensing. These authors, relying on their own work as well as the work of Cornelison, asserted they had located the “actual third line.” Indeed they had. They published a map showing the “actual third line” drawn through Cornelison’s site, exactly where Caruthers had placed it 150 years earlier.