John Eager Howard’s Letter to John Marshall

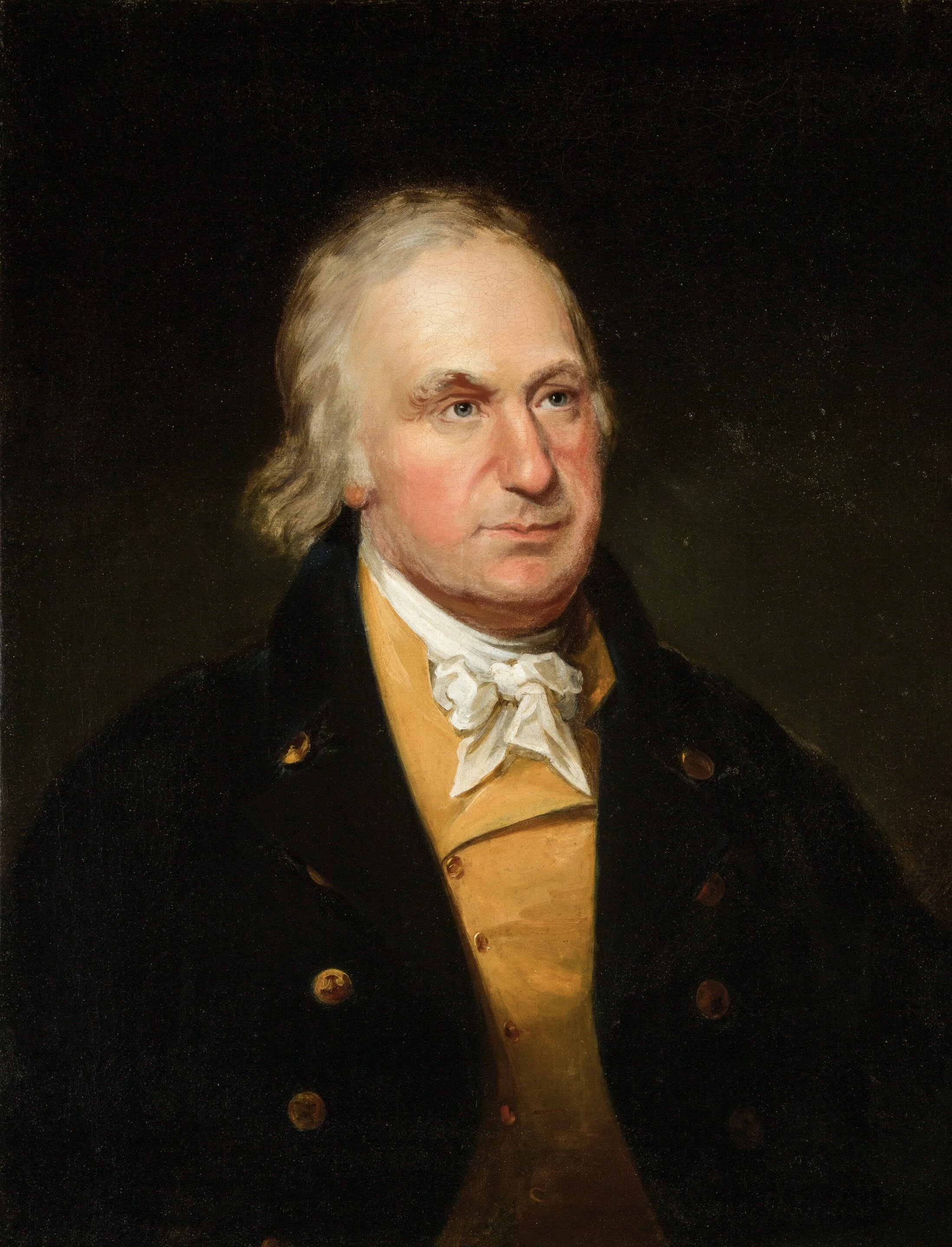

John Eager Howard was one of the heroes of the Revolution. Acclaimed as perhaps the best regimental commander in the war, his actions at Cowpens and Guilford Courthouse were decisive. After the war, he went on to a distinguished public career, including service in the Continental Congress and three terms as governor of Maryland.

Unlike many of his colleagues, Howard never took the time to write a memoir of his wartime experiences. He needed no self-serving narrative to burnish his accomplishments. His record, truly, spoke for itself. He left some scattered correspondence dealing with his service in the war. The most frequently quoted example was a letter to Henry Lee, IV, Light-Horse Harry Lee’s oldest son, responding to a series of written questions dealing with Cowpens and Guilford Courthouse.

The younger Lee wrote that he received Howard’s response shortly before he published his book, The Campaign of 1781 in the Carolinas, a spirited riposte to what he perceived as numerous slurs on his famous father by William Johnson, author of the first biography of Nathanael Greene. Lee’s comment dated Howard’s letter to 1824. Lee quoted extensively from Howard’s letter; see especially the footnote on pages 96 to 98. A later author relied on different quotes; see Elizabeth Read, “John Eager Howard: Colonel of Second Maryland Regiment—Continental Line,” in The Magazine of American History for October 1881. A modern author, Lieutenant Colonel John Moncure, reprinted the entire letter in Appendix C to his 1996 book, The Cowpens Staff Ride and Battlefield Tour.

Howard’s 1824 letter contained a great deal of valuable information about Cowpens and Guilford Courthouse. Howard, after all, was a central figure in both, placing him on a dais shared only by the likes of Robert Kirkwood and William Washington. His recollection was not perfect after 40 years, so his letter to Lee, although a great resource, proved imperfect in some of its details. For example, Howard insisted Captains Triplett and Tate guarded his left flank at Cowpens, but in all candor, there is little doubt they were posted on his right. Even so, his letter remains the best, most authoritative source for the series of events leading to the brief retreat of the Continentals, their rally, and their subsequent vanquishment of Tarleton’s attack.

There is another letter from Howard with a huge potential for impact on the history of the southern war. This letter, much more difficult to access, has seen little light since its inception. In 1804, Howard wrote a letter to John Marshall, at the time Chief Justice of the United States and an author in the middle of writing his exhaustive, five-volume biography of George Washington, the first volume of which appeared in 1804.

The content of the letter to Marshall is important and revelatory, but the letter itself holds a fascinating story. A transcription of the letter appeared in the files of Guilford Courthouse National Military Park. I made scans of the transcription several years ago, when I was using a truly substandard phone, and the scans show its handiwork.

The transcribed letter may be accessed here.

The transcription states it is from an original in the Bayard Collection of the Maryland Historical Society, MS 109, box 4, file 2. The Bayard Collection has a digital index available on in the internet through the Maryland Center for History and Culture. The index has no record of a letter from Howard to Marshall. I contacted the Center, and the archivist I dealt with assured me he made a diligent search and there was no such letter in their records.

The John Marshall papers also have a digital index published on the internet, and the Marshall papers show no record of any such letter. So, a mystery. Where did the letter originate? What happened to the original? Had I found the transcription somewhere else, I might be tempted to believe the whole thing was a sham. But, the historians at the park are notoriously diligent. I cannot get to a place where I thought they fabricated a document. The conclusion I have reached is that the transcription was made a long time ago; this much seems obvious regardless of any problems. I believe it was deleted from the Bayard Collection years ago, long before any digital index was made, so it has never appeared in the digitization of the collection.

The mystery of the letter to one side, its contents are fascinating. The original letter was quite long, and the historian transcribed only those parts related to Guilford Courthouse. The most interesting point arrived on page one. Tarleton wrote that Webster’s attack on the right of the American third line was driven back by overwhelming fire from the Continental line. Howard disagreed, writing that Webster was checked by Lynch’s Virginia riflemen, Kirkwood’s Delaware Continentals, and “a charge by Washington’s horse.”

A charge by Washington’s horse? This was radical stuff, indeed. Determining Washington’s place on the battlefield has proven difficult. He was on the right flank on the first and second line engagements. In the middle of the third line fighting, he emerged to make a thunderous, heroic attack on the 2nd battalion of Guards. Where he was in the interim has challenged historians, and the literature is replete with assertions of his presence on the right, the left, and in the center. If he participated in the resistance to Webster’s assault on the right, this would represent a sea change in the thinking about the deployment of the American cavalry.

As I see matters, Howard was a far better commander than memoirist. Washington’s charge against the 2nd battalion of Guards was a landmark in the battle, remarked by everyone. Literally no one else has ever suggested Washington was part of the force that repelled Webster. It seems incongruous that a cavalry charge that broke a major British offensive would have done so completely under the radar. At this point, we have to say that Howard’s position fails for a lack of consistency with the other narratives of the battle. However, it is a fascinating idea.

Howard was more in tune with others in describing the repulse of the Guards by his regiment, the 1st Maryland. He said very little of what he accomplished. He gave Colonel Gunby credit for the order facing the regiment into the salient created by the retreat of the 2nd Maryland from the attack of the Guards. He noted that Washington “made the charge upon the guards at the time the 1st regiment had nearly closed with them.” Howard left no doubt the repulse of the 2nd battalion of Guards was a joint effort by the 1st Maryland Regiment and Washington’s cavalry.

As a final note, there is his version of the tale of Washington’s hat. There are several versions of the story in the literature, one more enchanting than the next. In brief, Washington, pursuing the fleeing Guards, advanced far forward of the American line. He spied Cornwallis, and left his formation to pursue the opposing general. At the last minute, an unlucky shot took off his hat. Well, what could he do? He could hardly be seen in proper combat with no hat. So, he broke off the chase, stopped, and picked up his hat. Cornwallis lived to win the battle. The officer who took over the pursuit of the Guards became misdirected, and the American counterattack ended. Personally, I love this story, and it saddens me to point out the obvious, that absolutely none of it makes any sense.

Howard told a version that, at last, made sense. At about the time the American counterattack was running out of steam, Washington was unhorsed. The officer who replaced him at the head of the cavalry charge was killed. The counterattack, already in trouble, faltered. This, finally, brought order to the chaos of conflicting stories. Although we lost much in the charm of the narratives, at least we have gained a story we can accept.

There is much in the transcription that warrants explanation. The unclarity was not helped by my poor scans. The original would be a great help in working through the problems. Note on page two where Howard refers to himself in the third person. Although done frequently in memoirs, it seems jarring in a personal letter. Until the original letter resurfaces from whatever private collection it finds itself presently, this transcription, poor as it is, is all we have.