The Haldane and Tarleton Maps of Guilford Courthouse, Part 1

In the world of fact and legend arising out of the Battle of Guilford Courthouse, the British military maps dominate the landscape. Every battlefield reconstruction has relied heavily on them. The revised third line reconstruction adopted by the Park Service was based almost entirely on a reading of these maps. There is no discussion of the battle, or the battlefield, that does not involve these maps. For all their importance, there are still more questions than answers.

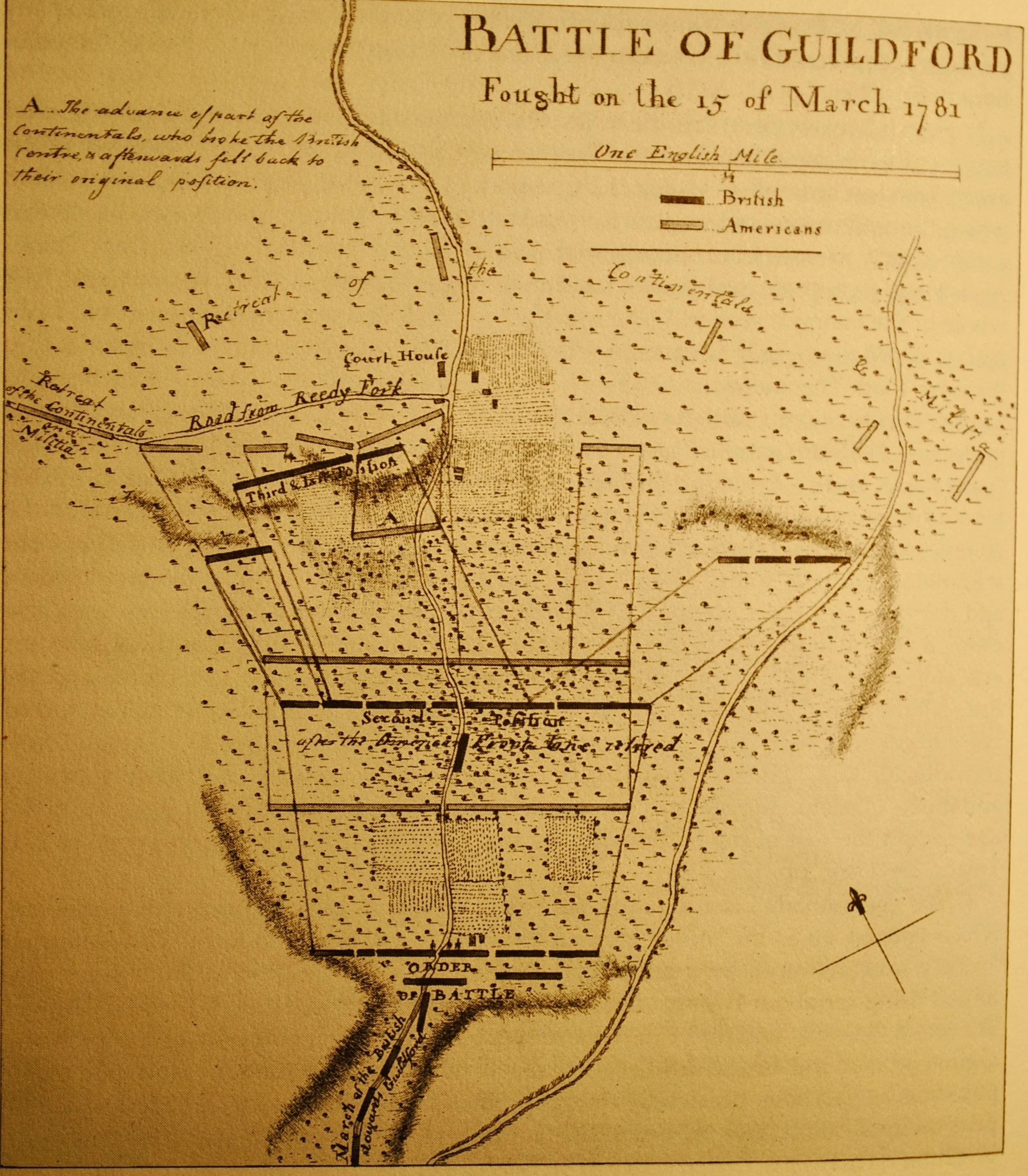

The most logical way to attack the problem of the maps is chronologically. The first map to appear in the literature was in the memoir of Lieutenant Colonel Banastre Tarleton, History of the Campaigns of 1780 and 1781, in the Southern Provinces of North America , in 1787. The map was prepared by England’s most prominent geographer, William Faden, and appeared in later collections of Faden maps, Atlas of Battles of the American Revolution, in 1793 and in the 1845 reprint edition. Here is the Tarleton map:

An interactive version of the map may be accessed here.

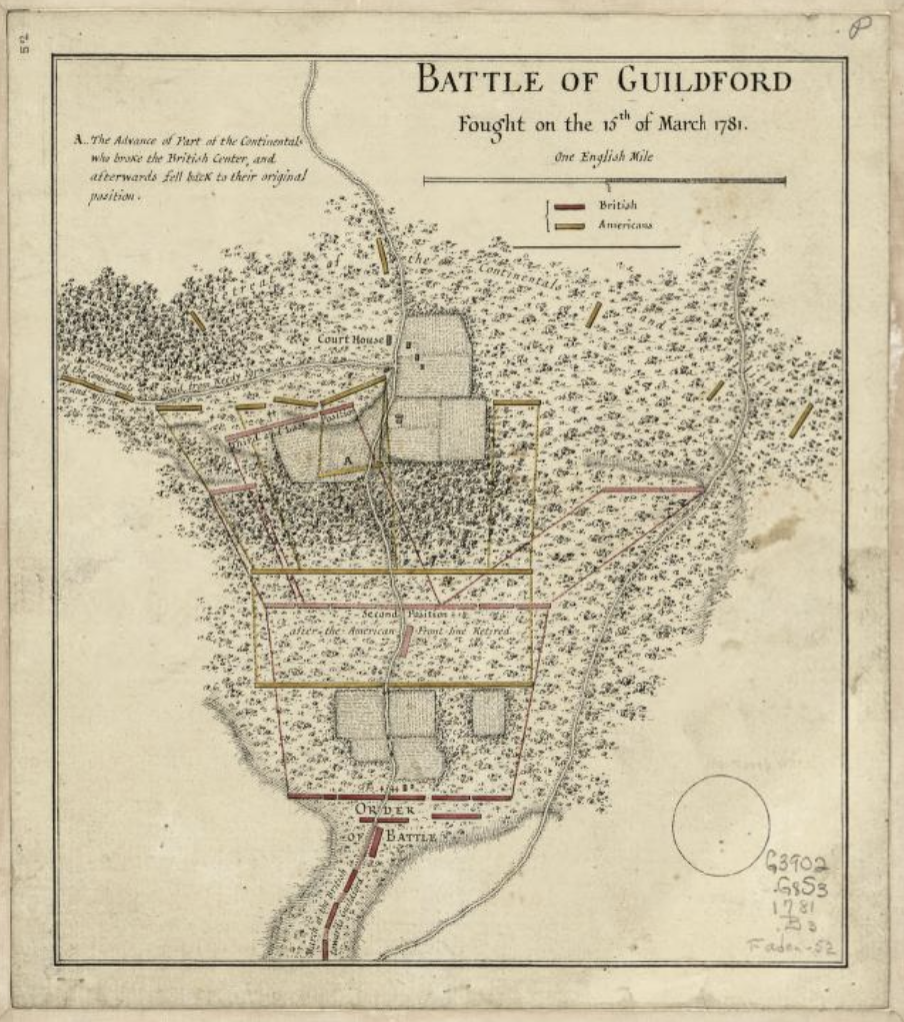

Tarleton never divulged the source of the information on his map. Many historians, displaying no understanding of Tarleton’s character, asserted Tarleton measured distances and drew the map from field notes he made during the battle (!??!!). Cooler heads have prevailed since then. A very similar map surfaced in the papers of Sir Henry Clinton on file in the William L. Clements Library of the University of Michigan. Two Guilford Courthouse National Military Park employees, Thomas Baker and Don Long, developed an attribution of the Michigan map to Lieutenant Henry Haldane, an engineer officer on Cornwallis’s staff. Baker and Long never published their work, but the outlines are clear enough. Haldane, as an engineer, was the most likely officer in Cornwallis’s entourage to draw a map. The document’s presence in the Clinton papers suggested it had been submitted with Cornwallis’s report of the battle, again pointing to Haldane as the likely author. Here is the Haldane map:

An interactive version of the map may be accessed here.

The Haldane map is nearly identical to the Tarleton map in all material respects. The conventional view has been that Haldane drew his map for Cornwallis, which the latter included to illustrate his report to Clinton. Tarleton then turned a copy over to Faden, who used it to prepare the final engraving that appeared in the Tarleton book.

The conventional analysis did not change with the revelation of another map in the series. Convention refers to this map also as a Haldane map. This third map stands between the Michigan Haldane map and the Tarleton map in its polish. Baker and Long never addressed this map, but if one accepts the map in the Clinton papers as first in the series, it seems obvious this map was a draft linking the rough work by Haldane to the final, polished effort in Tarleton’s book.The map is archived with the Faden maps in the Library of Congress, and there seems little doubt it was an early effort by Faden:

An interactive version of the interim map may be accessed here.

There was one more map, late to the party. Discovered much later, by all indications it was a rough draft of the rest. It varies in some ways with the others, notably in its use of many letters to indicate points on the battlefield, where the other maps limited their discussion to point “A.” Here is the rough draft:

An interactive version of the rough draft may be accessed here.

Once more, Baker and Long, and for that matter, Taylor and Durham, never addressed the rough draft. However, by anyone’s calculations, it was the first in the series, the rough draft that preceded the next one. The next one, however, is up for grabs. As Baker and Long put things together, the Haldane map was next, then Tarleton.

A more recent exposition looked at all four maps. In the Guilford Courthouse National Military Park: Archeological Overview and Assessment, Guy Prentice and Lou Groh reversed course. The rough draft remained the rough draft. But Faden’s work came next, starting with the interim map, which they saw as the engravers getting to work on the information in the rough draft. The final Tarleton map came next, showing the polish of Faden, the master engraver and mapmaker. Finally, the Haldane map in the Clinton papers was the last in the series, a handwritten copy by a later scribe, tucked into the Clinton papers by a well-meaning but misguided archivist.

Prentice recorded a conversation he had with the curator of the Haldane map in Michigan in 2012. He was told the Haldane map looked like a later, handmade copy of the Tarleton map. The curator suspected the Haldane map dated to 1790. He added that there was no evidence the map was included with Cornwallis’s report on the battle to Clinton. This point, of course, is true, and Cornwallis made no mention of a map enclosure in his report.

So, who’s right? Prentice and Groh allowed that the rough draft may well have been drawn by Haldane, for the same reason Haldane’s name keeps cropping up: as an engineer, drawing maps was within his jurisdiction. There is nothing else pointing to Haldane as an author of any of the maps in the series. Even so, the important point was which of the rest of the maps came first. Without any writings by Baker and Long, all we can do is surmise about their attribution of the map in Michigan as the first of the printed maps. In all fairness to them, the curator of the Michigan collection is a better source, and if he concluded the map in his library was the copy, and the Faden map the original, we would all do well to accept his decision.

And, finally, there it is: the solution. The winning answer was rough draft first, then interim map, Faden, and finally Michigan. Count on it.