William P. Brandon and the Third Line at Guilford Courthouse

This page continues the discussion of the placement of the third line of battle at Guilford Courthouse, begun on the page entitled “Hunting Creek.” I take issue with the second reconstruction, specifically its placement of the third line of battle on the east side of Hunting Creek. This was an error; the third line stood on the western bank.

The roots of the second reconstruction went back to the 1930s. William P. Brandon served in his career as the park’s historian and superintendent. In 1938, he wrote a paper entitled, “The Axis of the Battle of Guilford Courthouse.” His purpose was to determine the course of the fighting at Guilford Courthouse. Everyone knew the outline: Greene formed the Americans into three lines of battle. Cornwallis attacked, moving through all three American lines, until, at last, Greene ordered a retreat. Cornwallis’s course was marked generally by. Historic New Garden Road, also known in its eighteenth-century name as the Great Salisbury Road. The road still exists, for the most part in its ancient roadbed.

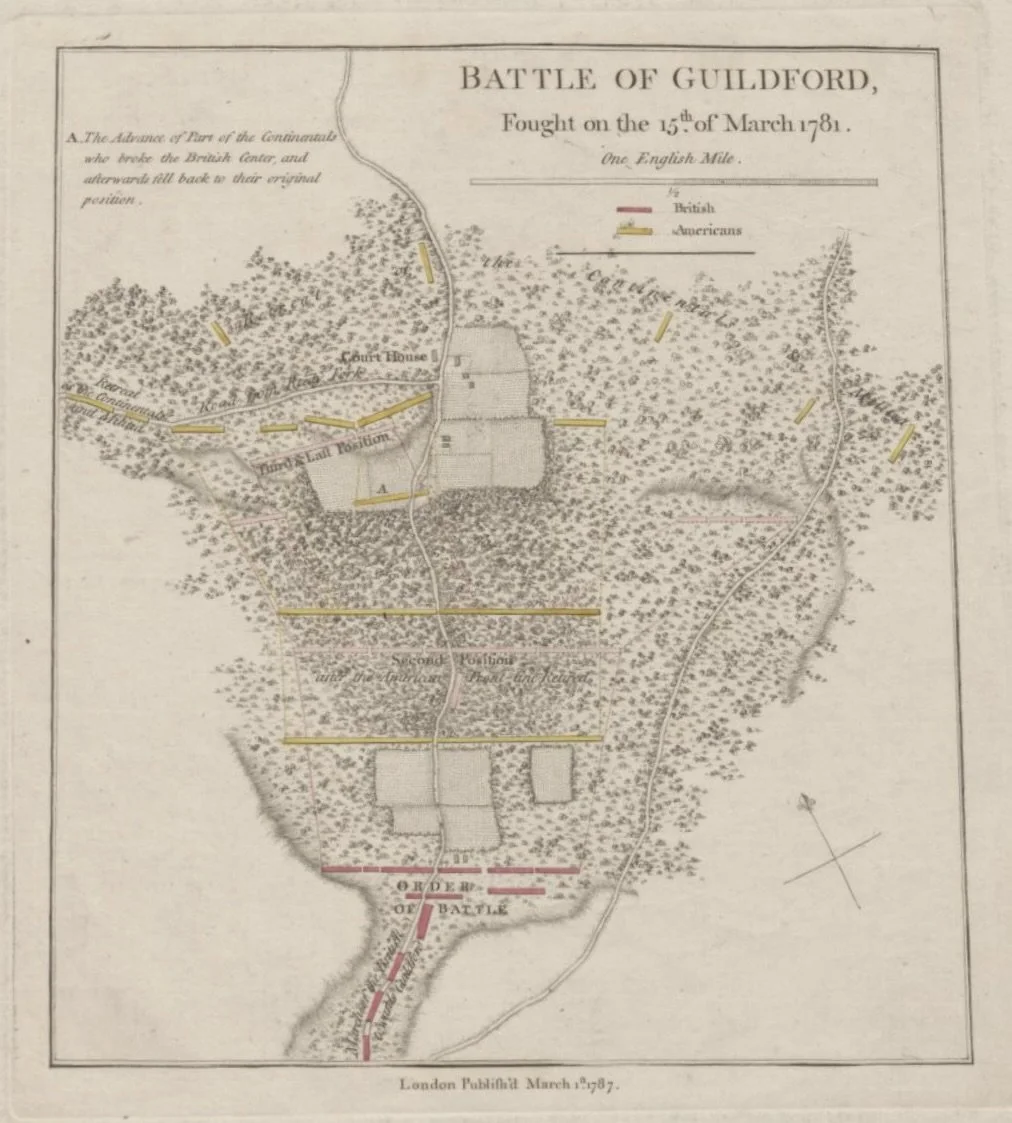

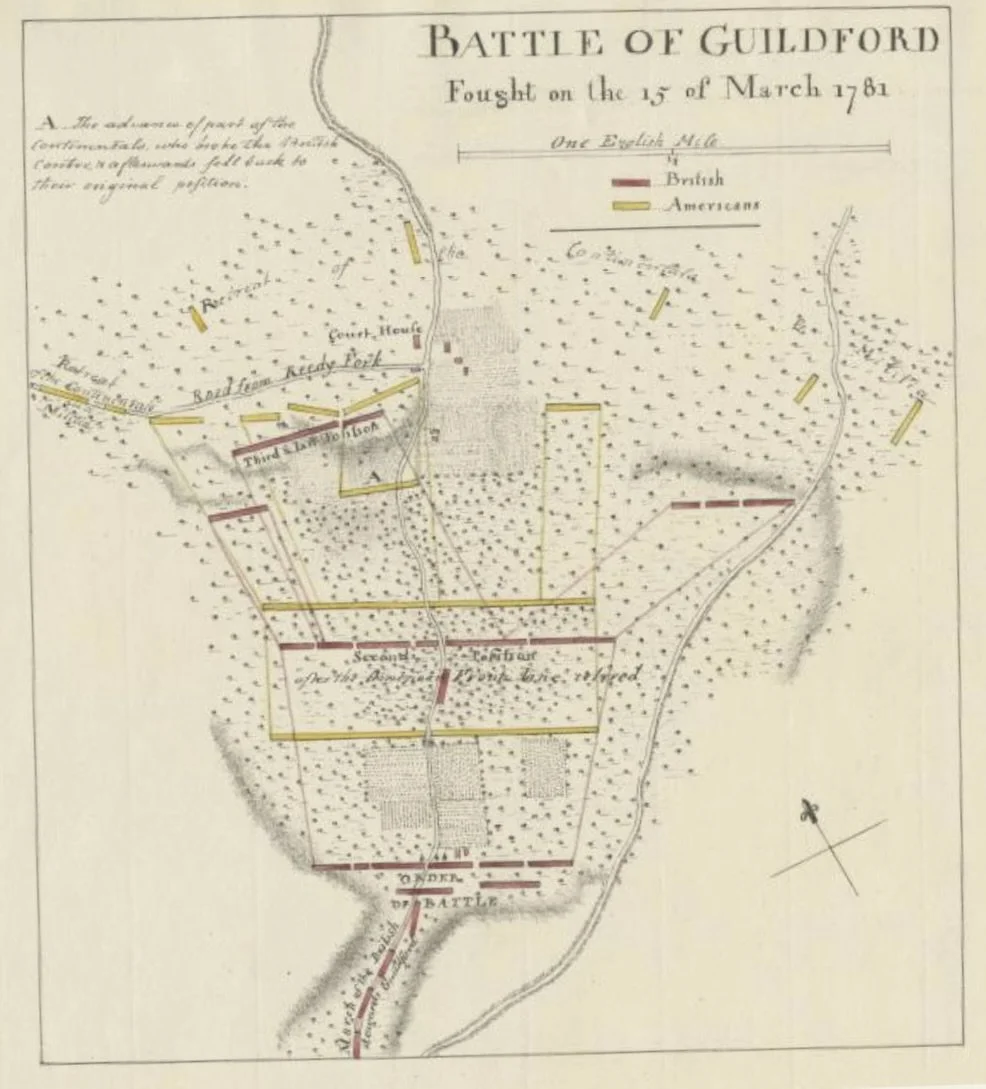

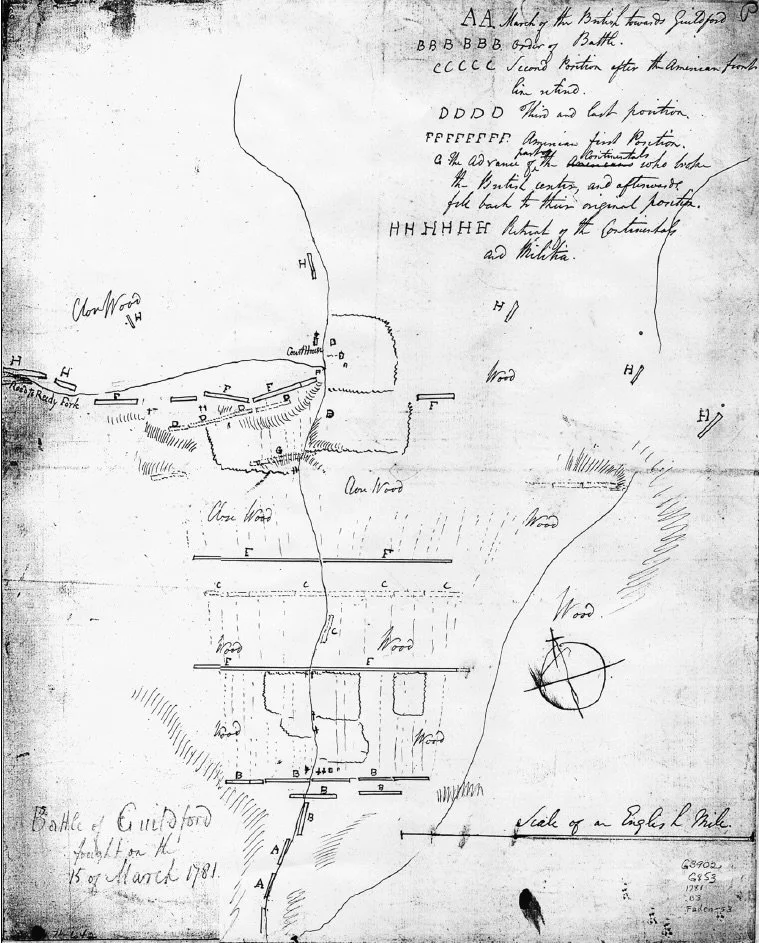

With so much known, what was the question Brandon wanted to solve? The problem lay in the few known maps of the battlefield. When Brandon wrote, the only contemporary map known to exist was the one printed in Tarleton’s memoir, History of the Campaigns of 1780 and 1781, in the Southern Provinces of North America, published in 1787. Tarleton’s map generally displayed the buildings and landforms of the battlefield. The great discrepancy was in direction. The map had a directional arrow pointing north, but the arrow was misdirected by fifty degrees. The error seemed overwhelming; could we rely on the only eighteenth-century map of the battlefield?

Brandon carefully considered the available memoirs of the battle. He compared the terrain features on the map to those on the ground. At bottom, he concluded the Tarleton map was wrong in its indication of direction: “the inescapable conclusion . . . is that in his indication of direction the Tarleton. map is in error.” However, this fact did not rule out the map entirely. The depiction of land and buildings was generally acceptable. It was here that Brandon left the quote for which his paper is now remembered: Tarleton’s map “is surprisingly accurate in many particulars, particularly as to distance.”

“Surprisingly accurate” was not a ringing endorsement. In fact, it was a backhanded swipe, saying, in effect, “given all the problems, the map actually managed to get a few things right.” A reminder that even a broken watch is right twice a day.

Even its pale endorsement of distances on the Tarleton map has problems presently. Brandon wrote from the information available at the time, which was that the map “was, presumably, based upon field notes, or sketches, or both, taken by Tarleton in the field, and may have been drawn by him.” Actually, Tarleton did nothing of the sort. The map in his book is a copy of a map attributed to Lieutenant Henry Haldane, an engineer officer on Cornwallis’s staff. The original of the Haldane map is in the Clinton papers, in the William L. Clements Library of the University of Michigan.

Brandon based his endorsement of the distances on Tarleton’s map by reference to what he called fixed points. Two were especially important: the original Guilford County courthouse and the Hoskins House cabin. As to the first, later generations have acknowledged that the site has been lost, and was lost at the time Brandon wrote.There is a traditional view of the matter that places the location near Tour Stop 6 on the park’s tour road. Archaeology conducted since the 1970s has failed to confirm the location.

As to the Hoskins House, in Brandon’s time, people felt the existing house dated to the time of the battle. Subsequent archaeology has dated the existing building to no older than around 1810. There have been no Revolutionary War-era household artifacts uncovered on the site. John Hiatt, a Park Service historian, properly concluded that the buildings interpreted as the Hoskins House and an outbuilding may have been a house and an outbuilding, or, equally well, two farm outbuildings.

The archaeology has sunk Brandon’s assertion of accurate distances between these “fixed points.” The points were far more fluid than he could have realized. Nevertheless, the cornerstone of the battlefield’s second reconstruction is a belief in the immutable, bedrock accuracy of the Tarleton and Haldane maps, a belief traced to the Brandon paper. The belief is utterly without foundation.

The Brandon paper is on file at Gulford Courthouse National Military Park. I have made a digital copy of the text, and for the first time have posted it, to make it available to everyone. For anyone with an interest in the battle, in particular, in the debate on the location of the third line, I encourage him or her to read Brandon’s paper and draw their own conclusions.

The paper may be accessed here.

Finally, a footnote. For reasons not completely clear, Brandon sliced and diced his data a second time in the same year. Also in 1938, he authored, “The Tarleton Map of the Battle of Guilford Courthouse: A Critical Study.” The paper used the same methodology and reached the same conclusions. I have also obtained a copy from the park, and I have posted it to make it available to everyone. Both papers are exactly as I received them. The second paper, in particular, has a great deal of handwriting on it, apparently from someone attempting to correct some of Brandon’s misconceptions. In this paper, the key quote is rendered: the Tarleton map “is surprisingly accurate in most details, particularly as to distance.” Again, not a ringing endorsement.