The Thomas Johnston Map of Guilford Courthouse

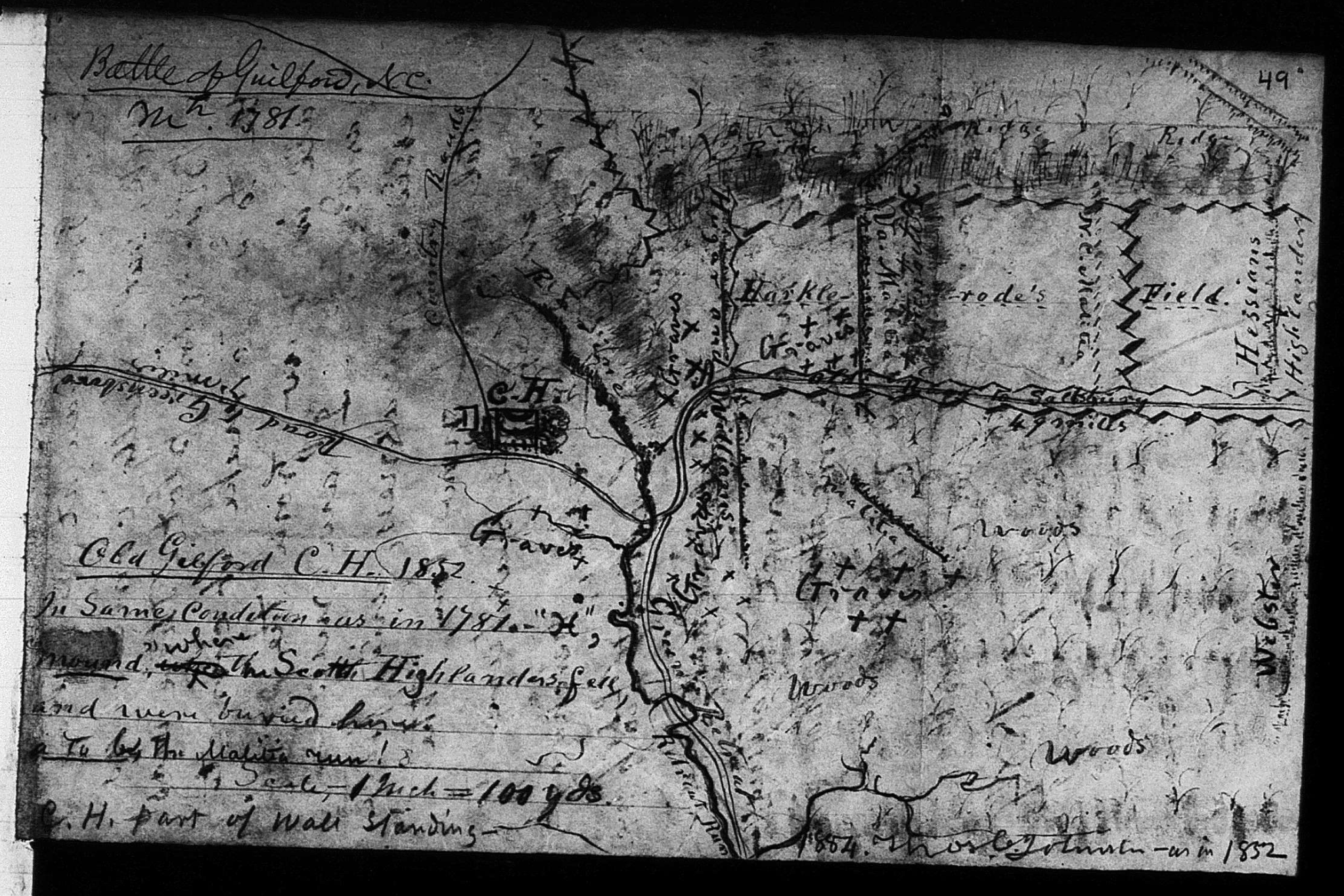

Of all the historical maps of Guilford Courthouse, the one prepared by Thomas Johnston may be the most unusual. Like most, it is a sketch, an especially crude one. The orientation is all wrong. North on the ground is on the left side of the map, so the British moved from right to left. Greene retreated from the center to the bottom of the page.

The dimensions of the map features are also wrong. The lines of battle are mere suggestions, and what is on the map does not even approximate the size of the actual formations.

The most intriguing aspect of the map is its date. The top left asserts it is a map of the “Battle of Guilford, NC, Mar. 1781.” Farther down on the left, it said something completely different: “Old Guilford C.H. 1852 In same condition as in 1781.” Okay, that’s actually a lot different, but it gets more convoluted. On the bottom right, I read the text to say, “1884. Thomas Johnston—as in 1852.”

The map is in the Lyman Copeland Draper Collection of the Library of Congress, at reel 3, volume 3, and this is the key to much of the mystery. Lyman Draper was a librarian and historian from Wisconsin who developed an extreme interest in the Revolutionary War in the western theaters, north and south. He interviewed people and collected documents almost obsessively, amassing thousands of pages of material in the late nineteenth century. His southern investigation led to his master work on the battle of King’s Mountain, King’s Mountain and its Heroes, a massive undertaking like nothing seen before, almost 700 pages of intense discussion of every conceivable aspect of the campaign.

Putting the pieces together, at some point, Draper interviewed a man named Thomas Johnston, who had visited the site of the Battle of Guilford Courthouse in 1852, and prepared a sketch map of the site. Johnston believed the site looked as it had in 1781, and documented his belief. He meant the battlefield, not the courthouse, and in this he was correct. The battlefield consisted of woods and farmland in 1852, essentially unchanged since 1781. The courthouse, however, had deteriorated significantly, as Johnston noted at the lower left corner of his map: there was “part of wall standing.”

Draper apparently talked to Johnston in 1884. As noted at the bottom right of the map, the date appears, with Johnston’s signature, and the notation that the appearance in 1884 was “as in 1852.” Again, he was correct, and the general appearance of the land had not changed by 1884. I read these notes to say Johnston drew the map in 1852, then authenticated it for Draper in 1884.

The Johnston map provides very little use for historians of the battle. Drawn by a later visitor with minimal mapmaking skills, it adds very little to the fund of knowledge about the battle. However, it has entranced people with an interest in locating gravesites on the battlefield. Johnston noted “graves” near the Hoskins House, in the fields west of the house, and in the curtilage of the courthouse.

The graves at Guilford Courthouse have proven challenging. There have been stories in the literature for hundreds of years, but few actual discoveries. At least, few that we know of. While many people have left anecdotal records of finding remains, archaeological proof has been elusive. One reason, I suspect, is secrecy. John Durham, for many years the park’s official historian, documented finding several burial sites. In his 2004 paper, he wrote of finding a mass burial site with stone markers east of Hunting Creek and north of the park’s tour road, following a severe ice storm in 2003. While he noted the site in his paper, he never seems to have made it public. The burials, and the gravestones, are not visible today.

Secrecy seems to have been Durham’s plan for dealing with burial sites. He was concerned about relic hunters disturbing the sites. In a 2007 newspaper interview, Durham stated that ground-penetrating radar had confirmed the site of a mass burial, twelve feet by eighteen feet in dimension. He refused to state the location, citing concern over relic hunters. Even so, he may have maintained an excess of secrecy. I had a telephone conversation with a Park Service archaeologist in late 2023 who had spent the summer digging for burial sites, unsuccessfully. He was puzzled when I brought up Durham’s interview and had no knowledge of a GPR-confirmed mass burial site.

So, the key question: are the gravesites on Johnston’s map real or imagined? He seems to have done a very good job recording the traditional sites of burials repeated by the people who lived in the area. However, and sadly, the archaeologists are telling us that these stories may not be entirely real.